Section Branding

Header Content

The James Webb telescope had 344 'single point failures' before launch. Then, success

Primary Content

This week, we got a new view of space. And it was epic.

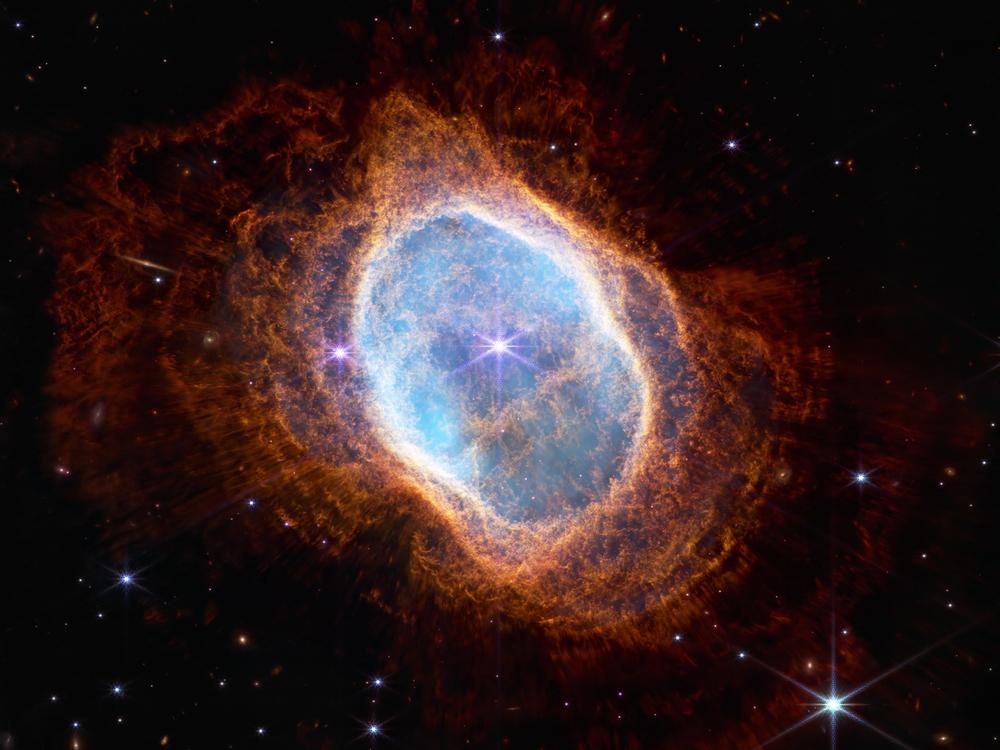

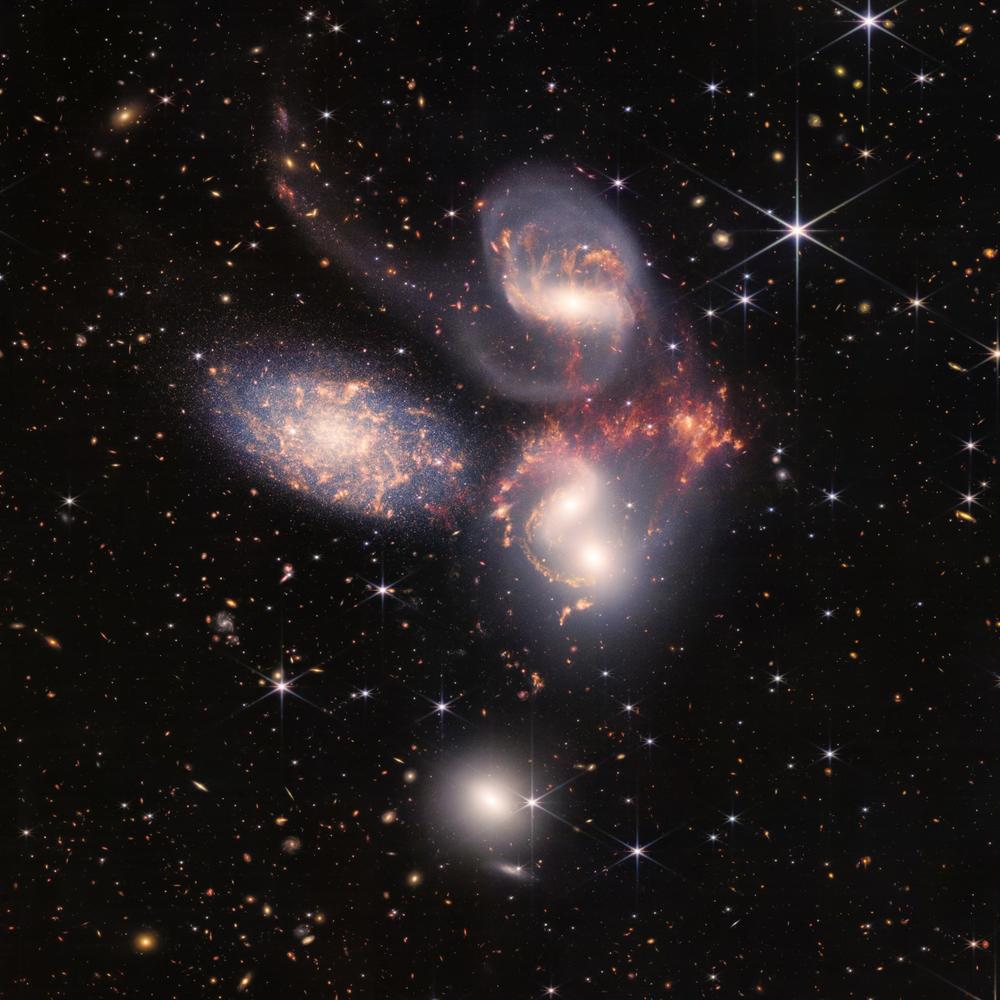

Cosmic cliffs of glowing gas, spinning galaxies, dying stars. The James Webb telescope caught those images of ancient history — billions of light years away — showing what the universe looked like when it was just forming after the Big Bang.

Some 20,000 people worked on the project for almost two decades, including engineer Bill Ochs, who has been the project manager since 2011. He joined All Things Considered to share the journey to this monumental snapshot in time.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

On what the project first looked like when he joined

When I came on board, they had just gone through an external review and it was basically concluded that they weren't going to make their current launch date, which I think at that time was 2013. We didn't have enough money.

So when I came on board, I was asked to go ahead and put together a re-plan, which was quite challenging because, you know, you're brand new onto something. To re-plan a mission of this complexity is a pretty steep learning curve. The complexity of this mission and testing it on the ground made us understand we really needed a little bit more time.

On the difficulties of keeping faith for such an ambitious project

In all honesty, I don't think I ever got to that point of really feeling like, hey, it's never going to work. I did hit my retirement age at one point [three years ago], and I thought, you know, maybe I should just retire. And then I'm like, no, I got to see this out to the end.

But that was it. I mean, I tell folks all the time. The type of words I never heard on this project in the 11 1/2 years that I have been here is "give up", "failure" — never heard those words. It was always, "Hey, we got an issue." Whether it was a design complexity issue or, in this case, we did have some mistakes that were made: How do we correct this? How do we make sure this doesn't happen again? And how do we move on?

On the moment it all came together

Well, it actually came in steps. So I really wasn't worried about the launch. The launch vehicle team was outstanding. But those first 2 1/2 weeks of deployment, that's probably the highest anxiety level that we had. I'm a pretty laid-back person. I've done operations before, so I'm pretty calm throughout the whole thing. But definitely, the anxiety level was up.

Prior to launch, folks talk, we had 344 single-point failures. A single-point failure means if this one thing fails, we could potentially lose the whole mission. And a majority of those single-point failures were going to be retired through that first two weeks or so of deployments. So when you think about it, anything in that first two weeks could have maybe taken us out.

When we got through the first two weeks, there was a big sigh of relief when we deployed that final mirror wing. Now you go through a period of checking out the rest of the spacecraft itself, and now we get ready to start aligning the mirrors. But there were 155 motors on the backs of these mirrors to make them function properly for us to do the alignments. Every single one of them worked. Every single one of them survived.

On his reaction when the first images started coming in

So the images that we released on Tuesday, I only saw a preview of a couple weeks ago. So the real images were the engineering images that we took during the mirror alignment phase. And if you saw that, the first image that we released that showed the perfectly focused star. That was actually a cropped image.

But when you looked at the entire image, it was like, "Yeah, OK, that's cool." The star is focused. Let's look at those galaxies in the back. And one of our engineers/scientists started counting. And in that first image, he counted 250-plus galaxies and then made a little photo montage of each of the galaxies. I started carrying this stuff around on my phone. They were like my baby pictures.

Instead of pictures of my grandson, I'm showing people pictures of galaxies. And the structure that you could see was amazing. If you think of Webb in car terms, this thing's a Ferrari or a Lamborghini. Now, we're probably getting close to where we can go into second gear. So at that point, we were barely in first gear, and we're still already seeing this amazing stuff.

On witnessing the world's reaction

Oh, it's amazing. From the day we launched, we started getting reactions from folks all over the world of how touched they were by this, and how excited they were. I participated in a National Park Service/NASA Dark Sky Festival at Death Valley National Park in February, and myself and one of our scientists gave the keynote address.

Afterwards, we're hanging around, and we're talking to folks, and they're asking questions. We had this one lady come up to us, and she said, "Hey, I drove three hours to get here only to hear you guys speak. This is such great news in this world full of trouble." And she started crying when she was talking to us.

And then, just today, there was a special about Webb last night on TV, and one of my communications folks got an email from a rancher in Idaho saying how him and his family were so touched by it. I mean, they now appreciate the fact that they're really in a good dark sky area more, and they can go out at night and see so many stars. It just gave them a greater appreciation. But again, it was related back to [the idea that] with so much trouble in the world, this is just a ray of sunshine.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.