Georgia High School Musical Theatre Awards at 8p

Section Branding

Header Content

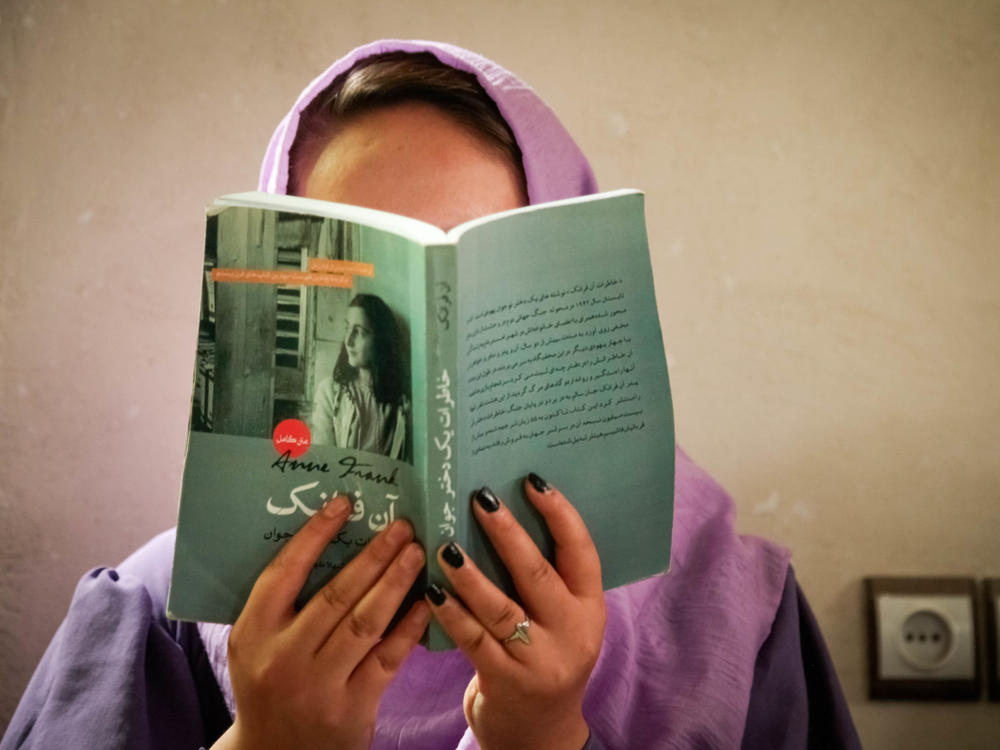

In a secret Kabul book club, teen girls find comfort in the diary of Anne Frank

Primary Content

KABUL, Afghanistan – In the year since the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, they have used their muscle to restrict the education and curiosity of girls. They've been banned from high school, told to cover up and stay home. But in one secret book club in Kabul, about a dozen teenagers are defying the Taliban to continue learning – and along the way have connected to a girl from a different time and place who was also forced to live her life in secret.

"She had hope. She was fighting. She was studying. She was resisting her fate," says Zahra. She's in the basement of a building on a side alley on the outskirts of Kabul where the book club met on a recent August day with two young volunteers who act as facilitators, steering the conversation and asking questions.

Zahra is speaking of Anne Frank.

The girls are reading and discussing the teenager's famous diary, which she began writing at age 13. And they are struck by the parallels: Just like them, Anne was only a kid – one who was starting to learn about the world – when she was forced into hiding because of a violent, oppressive government.

Another book club member summarizes the diary at a facilitator's urging: "In the beginning Anne has a good life, but after Hitler takes over, he places strict laws and regulations against Jews. They go into hiding. They can't make noise. They have to walk softly."

Four volunteers set up this weekly book club for teenage girls shortly after the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August last year.

(NPR is only using the first names of the girls to protect them from any Taliban reprisals for violating the education ban and not identifying the club's organizers, who fear the Taliban could shut down the book club and punish them for educating the girls.)

The origins of the secret book club

The girls in this book club come from a heart-wrenching cohort: Nearly all of them have survived suicide bombings over the past few years. Some were wounded; others suffered psychological harm. Some lost family. They lost friends. They all belong to a persecuted ethnic minority called Hazaras. Living under the Taliban's rule has added to their hardships..

The four volunteers are young men and women who have worked in education and community service for years. They hope the girls will be able to process the events of their own lives through reading and talking about the classics of Persian and Western literature, translated into Farsi.

"We come here, we talk about the books, and then we understand ourselves, our thoughts," says one of the young book club members, Arzou. "It is like, so amazing."

Some of the books are intended to show the girls how other minorities have survived persecution – or not – through personal stories of resistance and suffering, like Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl and The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank.

Bringing a Jewish voice to Kabul

It is a remarkable effort in a culture and region where there have been no substantial Jewish communities for decades and where clerics have often maligned Jews, without evidence, as seeking to undermine Muslim communities and Islam itself.

But the Hazara volunteers who lead this book club understand the European Jewish experience differently: a minority that was once unspeakably persecuted as part of the Nazi effort to exterminate the Jewish people, with millions killed, but which has since thrived. They hope the girls will see that too.

Volunteers who facilitate the book club assigned Frank's diary to the girls in late July. They agreed to meet weeks later with NPR to talk about it.

The book, which has been translated into over 70 languages and sold some 30 million copies, was translated into Farsi by a 61-year-old Afghan refugee named Khalil Wedad who lives in the Netherlands.

Wedad said when he first came across the book in a class he attended on Dutch language and culture, he was taken by how Anne Frank's story of a girl in hiding resonated with the experience of many Afghans living through decades of war. He hoped that if he were to translate the book, Afghan girls would see themselves in her story.

Wedad told NPR that he was supported by the Anne Frank House, which oversaw the translation and paid for publishing about 1,500 copies.

"At first it may seem surprising that these girls relate so powerfully to Anne Frank, but for young people who experience terror and oppression who have to hide for their lives, there's somehow comfort to know they're not alone," says Doyle Stevick, executive director of the Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina. (The center is the official partner of the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam).

"The diary helps us recall our common humanity no matter what our differences may be," Stevick says. "Anne's strong spirited determination not to give into despair has inspired people around the world."

In 2005, after the Farsi edition of the book was published, Wedad said he traveled back to Afghanistan and held small meetings with journalists and civil society activists to introduce the book. He even held readings with Afghan teenage girls.

Wedad said he hadn't heard about the secret book club but was pleased to learn that young Afghan women are finding meaning in Anne Frank's story. "It feels like his mission was kind of fulfilled," Wedad's son Khaled told NPR, translating for his dad, who does not speak English.

'I think Anne Frank is ... a friend for me.'

Arzou, one of the book club participants, said it was the first time they had read the firsthand account of a teenage girl living through extreme hardship. "I think Anne Frank is like, as a friend for me," she said.

"Something is in common with me and Anne Frank," Arzou says. "We are both the victims of war. I mean, Anne Frank is suffering from war and I am too. And Anne Frank cannot go to school, cannot, like go out very freely. And I have the same situation."

Like Anne Frank, Arzou says, "we are just in a dark place and there isn't any light," she says. "And we don't understand what would come after this."

Before the Taliban came to power, Arzou says her grades were so high that she expected to apply to colleges abroad to study computer science. That dream is over.

She's 17, but her hair is streaked with gray – a startling sight set against the pimples on her teenage face. She thinks the grays are because she holds in the suffering she's experienced.

But she says she's learning that other people, like the Jews of Europe, like Anne Frank, lived through worse.

"I found the Anne Frank situation more harder than us," Arzou says. "They cannot go out, and every minute they are thinking of being free, but in the end, they even die. So if I think of my situation. I am very grateful because I have these people that I can share my ideas with. We can gather together and talk about anything that we want."

Another girl, 17-year-old Masouma, wearing a lavender headscarf and purple robe, raises her hand to talk. She says she relates to how Anne Frank faced the real fear that she'd be killed even as she wrote about her typical teenage problems, including her crush on a teenage boy who shared their hiding place and her clashes with her mother.

"I loved the whole book. It was like a friend of mine telling me her pain, her stories. When she called her diary Kitty, I smiled and I imagined that I was Kitty, and that we are best friends," Masouma says smiling.

Masouma is referring to this moment in Frank's diary: "All I think about when I'm with friends is having a good time. I can't bring myself to talk about anything but ordinary everyday things. We don't seem to be able to get any closer and that's the problem. Maybe it's my fault that we don't confide in each other. In any case, that's just how things are, and unfortunately they're not liable to change. This is why I've started the diary."

"To enhance the image of this long-awaited friend in my imagination, I don't want to jot down the facts in this diary the way most people would do, but I want the diary to be my friend, and I'm going to call this friend Kitty."

Masouma says she admires Anne Frank for trying to have a sense of perspective: She was sad because she couldn't go to school in hiding. But she knew it was worse out in the world. She wrote in her diary in 1942 about Jews being transported to camps: "We assume that most of them are being murdered. The English radio says they're being gassed. Perhaps that's the quickest way to die."

And she says, Anne Frank didn't give up on education. She tried to continue her education in secret, even taking a shorthand course by correspondence. Masouma is trying to keep up her education as well.

Despite the Taliban's ban on secondary education for girls, Masouma and other girls were sneaking into a high school that was secretly letting them attend the boys-only classes. They were ducking into the school gate in tiny numbers, hoping they wouldn't be noticed.

"But there were too many of us," Masouma says. She says the school principal feared local Taliban security forces would notice the girls coming in and out, and so they were told to go home. "The girls were all crying," Masouma recalls. "My sister is still traumatized and now she doesn't want to try to get an education."

Masouma and the other girls say they find comfort in Anne Frank's diary, even though they know how it ends. Anne Frank died of typhus in 1945 in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after her family was betrayed and their hiding place revealed. She was 16.

Zahra, the young woman who described Anne Frank as resisting her fate, says knowing the end didn't depress her at all. "Nobody knows how long I will live, or when I will die," she shrugs. "The only thing you can do is leave something behind for the world that gives your life meaning."

Like Anne Frank, who left behind her diary, published in 1947.

"Right now, the Taliban are in power," Zahra says. "One day, they will be gone. Maybe people will forget what they did to girls like me."

She says that she wants to write a book as Anne Frank did so the world will know about the teenage girls of Afghanistan as well.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.