Section Branding

Header Content

To save Jewish culture, American Jews turned to summer camp

Primary Content

Sadie Leiman is heading into her final summer at Camp Kalsman, on 300 acres in Washington state. She's 16 and started going to this camp as a toddler while her mom worked there. And she's looking forward to seeing friends and being on her own. But most of all, Leiman's looking forward to Shabbat – welcoming the Sabbath every Friday night.

"When you're at home, if you don't have, like, I don't know, 400 siblings – which most people don't – Shabbat is a very private thing," laughs Leiman. But at Camp Kalsman, she says, "it's so many people just dancing and singing and it's beautiful and it's spiritual and it's Jewish. It's just so fun."

For American Jews who are often used to being in a cultural minority, having that immersive experience can be life-changing. Which was kind of the reason this all started. In the wake of World War II, when European Jewry had been decimated and American Jews were moving from all-Jewish enclaves to more integrated suburbs, American Jewish leaders worried that their culture might not have a future. And so they turned to summer camps.

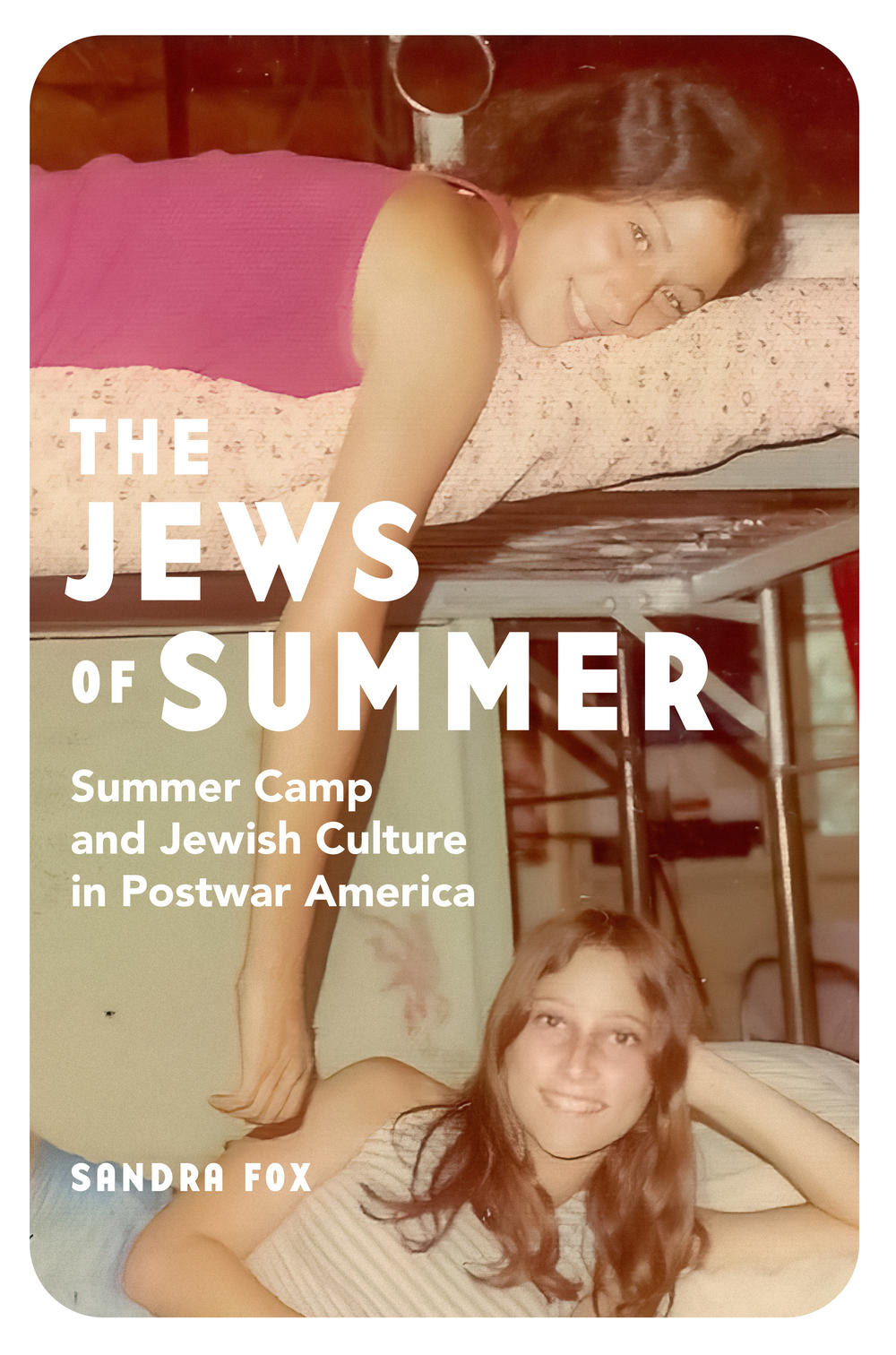

Sandra Fox, a visiting assistant professor at New York University, chronicled the mid-century expansion of these camps in her recent book The Jews of Summer: Summer Camp and Jewish Culture in Postwar America.

Fox says Jewish summer camps initially started in the 20th century with progressive reformers in the Northeast looking to take city kids out in nature, and to Americanize immigrants.

But Fox says the big boom happened after World War II:

"Jews, like many other white Americans in particular, return home from the war. And they receive benefits for veterans of World War II that kind of catapult them into the middle class after decades of building towards that. And in that new middle class milieu, Jews are moving to American suburbs."

But Fox says that as American Jews enjoyed this comfort and assimilation, there was a concern about what would happen to the Jewish traditions that had been maintained without much conscious effort in more segregated neighborhoods. And, she adds, there was another obvious reason that Jews were afraid for Jewish culture.

"The Holocaust had just happened," Fox explains. "And so in the shadow of the Holocaust, American Jews were incredibly anxious about the future of Jewish culture and Judaism as a religion and Jewish summer camps came to be seen as solutions to all kinds of communal ills, but in particular, the problem of assimilation."

Summer camps became a way to hold onto and rebuild Jewish heritage. But in attempting to maintain Jewish traditions, these camps created a whole new form of it. One huge component was embracing Israel and its founding as a source of pride.

"The idea was basically that Israel was something that could inspire American Jewish kids more than looking towards the Jewish past of oppression and violence in Europe," observes Fox.

Bunk names and activities were tied to stories from Israel's founding. Talent shows, like this 1963 "hootenanny" from Camp Massad in the Poconos, featured Hebrew versions of popular songs.

As air travel became more affordable, Fox notes that camps began bringing actual young Israelis, many of them just off their army service, to serve as counselors (and role models) for the young American campers, an exchange that continues to this day.

While Israel and its founding were highlighted, the fate of Jews in Europe was also something the camps acknowledged. Some had memorials to the Holocaust right on their grounds, or used Tisha B'Av, the summertime fast day commemorating the destruction of the temples, as an occasion to reflect on either the Holocaust in particular or the preciousness of life and Jewish practice in general.

As camps tried to make history come alive, there were pretty intense role-plays.

Flip Frisch attended Wisconsin's Camp Herzl in the 1980s, and remembers getting up in the middle of the night to reenact an escape from Nazi-controlled Europe – not the usual lighthearted summer camp activity.

"You had to have these papers and carry them with you at all times and be transported by rowboat in the dark and the back of a van with the seats taken out no windows," remembers Frisch. "And older kids pretending to be police and stopping you with flashlights in your face."

Frisch says they also marked Tisha B'Av by wearing all black, and writing letters as though it was their last day on earth.

Camps have largely abandoned those more dramatic (and potentially traumatizing) activities. But Frisch says, more than these very memorable recreations, she was struck by just living everyday life in a way that tied her to tradition.

"I can credit camp with my entire Jewish identity. The whole reason I stuck with Judaism was camp and the connections I made," says Frisch.

A recent Pew Research Center study found 40% of Americans raised Jewish attended one of these camps. Of, course some people go for a summer and never return. But some are like Frisch – who became a camp counselor and program director, and today works at her synagogue. Throughout the country, there are alumni networks, reunions, and a not-insignificant number of camp marriages.

In many ways, Jewish summer camps have changed since the early days (and since Frisch's time). Talk of Israel is definitely more nuanced – especially when it comes to the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. 16-year-old Sadie Leiman said that her camp's Israeli counselors lead a discussion about Israel.

"We put anonymous questions in a bucket and they just answer," she explains.

Those range from the non-controversial, "What's Israeli food like?" to questions that get at the intractable conflict that likely wouldn't have even been acknowledged at camps in years past: "Who's in the wrong?" and "What can we do to help?"

There are other differences as well. Intermarriage, a subject that sparked fears of a "continuity crisis" for American Jews in the 1970s, is now seen as a fact of life, says Sandra Fox.

"This fight against interfaith marriage doesn't really resonate with younger Jews, many of whom are choosing to intermarry and still raise their children Jewish," explains Fox. "They don't see it as a contradiction or a problem."

But even with these changes – or perhaps because of them – Jewish summer camps still produce kids with a strong sense of Jewish identity who are active in maintaining Jewish tradition. And are building traditions of their own.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.