Section Branding

Header Content

The Supreme Court meets Andy Warhol, Prince and a case that could threaten creativity

Primary Content

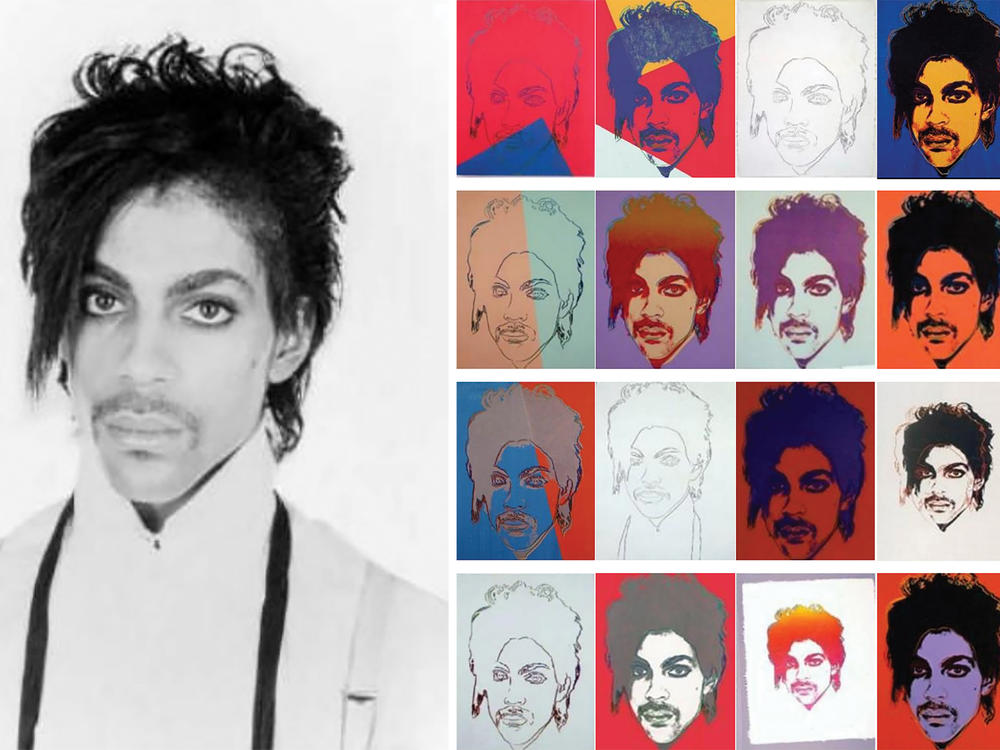

You know all those famous Andy Warhol silk screen prints of Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor and lots of other glitterati? Now one of the most famous of these, the Prince series, is at the heart of a case the Supreme Court will examine on Wednesday. And it is a case of enormous importance to all manner of artists.

On one side of the dispute is Lynn Goldsmith, famous for photographing rock stars and whose work is on more than 100 album covers. In 1981 Goldsmith was commissioned to shoot a series of photos of Prince for Newsweek. At the time the Purple Rain rock star was just starting to take off. Goldsmith photographed him in concert and invited him to her studio where she gave him purple eyeshadow and lip gloss to accentuate his sensuality and his androgyny. She even set her photography umbrellas to create pinpricks of light in his eyes. The result was an image that she would later say was a portrait of vulnerability. Newsweek didn't use the studio photo, opting instead to use the concert photo, and Goldsmith kept the other photos in her files for future publication or licensing.

Three years later Prince was a superstar, and Vanity Fair magazine commissioned Andy Warhol to make an illustration of Prince for an article it was running. In commissioning the work, the magazine asked Warhol to use as a reference point one of Goldsmith's black-and-white photos. The magazine paid Goldsmith $400 in licensing fees and promised in writing to use the image only in this one Vanity Fair issue.

There is no evidence in the record that Warhol knew about the licensing agreement. But in any event, he went beyond it and created a set of 16 Prince silkscreens, which he copyrighted, and one of which Vanity Fair used for the article. The silkscreen images have since been sold and reproduced to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars in profits for the Andy Warhol Foundation, a nonprofit that was set up after Warhol's death to promote his work and the visual arts.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair's parent company, Conde Nast, expedited a tribute, "The Genius of Prince," featuring many Prince photographs, and it paid the Warhol foundation $10,250 to run "Orange Prince" on its cover. Goldsmith received no payment or credit this time, and she eventually sued the foundation, claiming that Warhol had infringed her copyright, and that the foundation owes her potentially millions of dollars in unpaid licensing fees and royalties.

The foundation countered that Warhol not only copyrighted his iconic Prince series, but that his treatment was, in legal terms, "transformative" because his artistic rendering is very different from Goldsmith's original photo. The foundation asserted that in Warhol's version, not only did Warhol crop the image to remove Prince's torso, but he resized the image, altered the angle of Prince's face, and changed the tones, lighting and detail, in addition to adding layers of bright and unnatural colors, conspicuous, hand-drawn outlines and line screens and stark back shading that exaggerated Prince's features.

The result, according to the foundation, is "a flat, impersonal, disembodied, masklike appearance" that is no longer vulnerable but iconic. Essentially, the foundation is arguing that Warhol used a black-and-white photograph as a building block, in much the way that a collage artist might use slices of different photos in a larger work.

As you might imagine, each side has its experts, and indeed two lower courts disagreed on the matter. A federal district court judge found that the Warhol series is "transformative" because it conveys a different message from the original, and thus is "fair use" under the Copyright Act. But a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed, declaring that judges "should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain ... the meaning of the works at issue." If the Supreme Court agrees, the Warhol Foundation will have to pay royalties or licensing fees, and potentially other damages to the original creator, Goldsmith.

However the Supreme Court rules, its decision will have rippling practical consequences. So it is no surprise that some three dozen friend of the court briefs have been filed arguing on one side or the other, and representing everyone from the American Association of publishers and the Motion Picture Association of America to the Library Futures Institute, the Digital Media Licensing Association, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the Recording Industry Association of America and even the union that represents NPR's reporters, editors and producers, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

The outcome could shift the law to favor more control by the original artist, but doing that could also inhibit artists and other content creators who build on existing work in everything from music and posters to AI creations and documentaries.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.