Caption

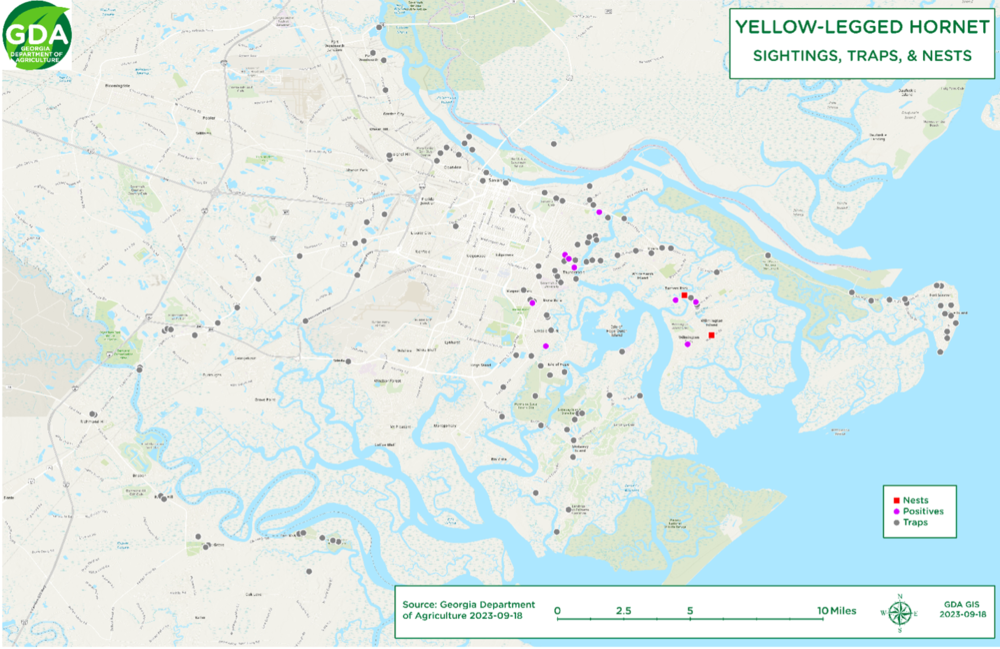

Georgia Agriculture Commissioner Tyler Harper speaks at a Wednesday news conference in Atlanta, standing next to a portion of the second yellow-legged hornet nest and a map of sightings in Chatham County.

Credit: Georgia Department of Agriculture